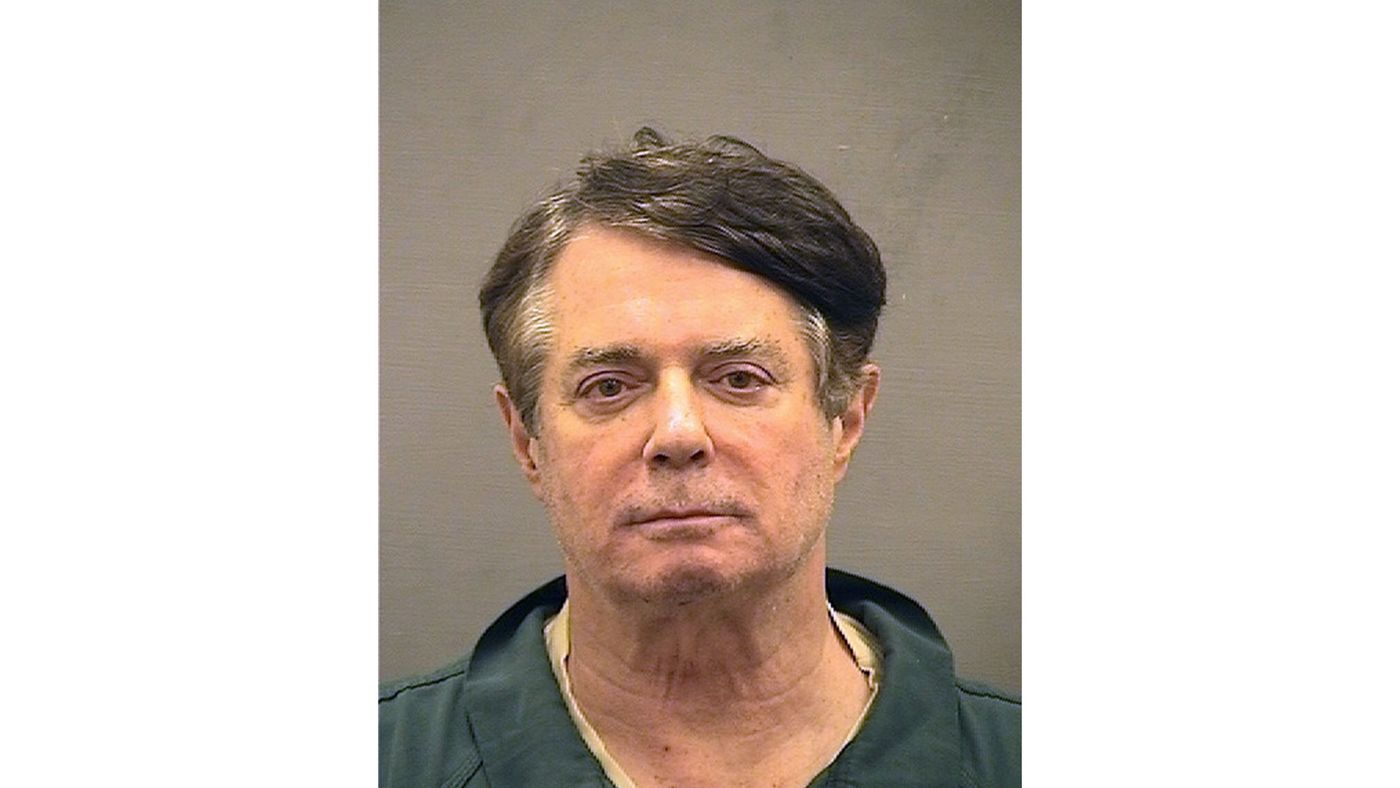

The D.C. Circuit doubled down Tuesday (July 31) on its denial of Paul Manafort’s plea to get out of jail.

Earlier this month, the former Trump campaign chairman lost his first round in the D.C. Circuit when he asked to be immediately released while the court reviewed his appeal of a D.C. district judge’s ruling that revoked his bail after his alleged witnesss tampering. On Tuesday, the court decided the merits of that appeal and delivered a TKO to the request.

The ruling came on the same day that Manafort began trial in Virginia on bank fraud and tax fraud. He has a second trial scheduled in D.C. this fall.

In a unanimous opinion by Judge Wilkins (joined by Judges Tatel and Griffith), the court relied on the highly deferential “clear error” standard of review to affirm District Judge Amy Berman Jackson’s ruling that Manafort was unlikely to abide by any conditions of pretrial release. Wilkins said the conduct that “loomed largest” was evidence suggesting Manafort had committed a crime during his release. He noted that Manafort “had been warned about skating close to the line” when he nearly violated a gag order by editing an op-ed about is Ukrainian business dealings but “went right past the line with the alleged witness tampering.” In February, Manafort allegedly sent multiple text messages and made unreturned calls to at least two witnesses in his case.

While the court affirmed Jackson, it did not embrace all of her reasoning and held at least a portion of it to be error. Jackson relied, in part, on a court order from the Eastern District of Virginia, where Manafort has his first trial, that told him to “stay away” from victims and witnesses in that case. Wilkins said Jackson’s “implicit finding” that Manafort violated that order was “problematic” not only because the Virginia order could cover entirely different witnesses irrelevant to the case in D.C. but also because the order itself was somewhat ambiguous. Nonetheless, the flawed reasoning did not undermine Jackson’s ultimate conclusion.

The D.C. Circuit’s opinion makes it clear—at least for now—that he won’t get a chance at reprieve from his detention while he goes to trial.

For court-watchers and procedural nerds, the court pointed out that it employed the clear error standard in this case because both sides asked for that standard—not because it has resolved what standard is appropriate. Indeed, Wilkins emphasized that the standard of review for the determination that a defendant is unlikely to abide by any conditions of release remains an open question for the court and left the resolution of such “thorny questions for another day.”

![]()